Serial killer narration is the hot sauce on the tuna casserole of a murder book. What would Thomas Harris’ Red Dragon (1981) be without the talking William Blake painting that keeps yelling at poor Francis Dolarhyde to pump iron and get jacked so women can’t threaten to snip off his penis with scissors anymore? Psycho (1959) stays firmly in third person limited point-of-view but its twist wouldn’t work if chapters didn’t keep dumping us into Norman Bates’ head while he has perfectly reasonable conversations with “Mother.” By the final chapter her voice has eaten his away like acid, a genuinely chilling end that works far better than Hitchcock’s closing square-up.

It’s almost impossible to read a murder book anymore that doesn’t include cuckoo chapters from the psychopath’s POV because they’re just so much fun to write. “Watch this!” writers say as they go full Method. “I’m going to totally channel the voice of a man who pretends to use a wheelchair but is really murdering children while dressed as a nurse in order to transcend gender and become immortal. I’m an artist! I can do anything!” But to do anything, there needed to be decades of work by writers as varied as Shirley Jackson and Richard Wright before someone could give us a serial killer book with Elvis wearing a chihuahua inside his pants.

It took a village to influence the development of novels written in the first person from a psychopath’s POV, and influences can be found in a lot of forgotten cupboards, but I feel reasonably confident saying that Edgar Allan Poe did it first in his murderer-narrated stories like “The Black Cat” and “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Narrated by gibbering, haunted men seized by psychotic rages, their brains boiling with guilt, these stories appeared in the 1840s, alongside the much colder and more calculating “Cask of Amontillado,” creating the template for killer-narrated books in which the fractured perceptions of their narrators shape the entire story.

Fyodor Dostoevsky makes a quick cameo here with his back-to-back Notes From the Underground (1864) and Crime and Punishment (1866) which experimented with unreliable POV characters who were losing their grip on their sanity, but in America the next notable book in the evolution of this subgenre was James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) which sold millions of copies and got everyone used to books narrated by murderers, even though Cain keeps his prose’s shirt tucked in and hair combed. Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940) makes no such concessions. The story of Bigger Thomas, a Black man who murders a couple of women, it’s entirely channeled through his haywire perceptions even though it’s in third person limited, with Wright deliberately setting out to shock his readers after being disappointed that his previous book, Uncle Tom’s Children, was one “which even bankers’ daughters could read and weep over and feel good about.” Native Son was a hit and Wright made it clear that he viewed his lineage as full bore horror. “If Poe were alive,” he said of the horrors of race relations in America. “He would not have to invent horror; horror would invent him.”

Buy the Book

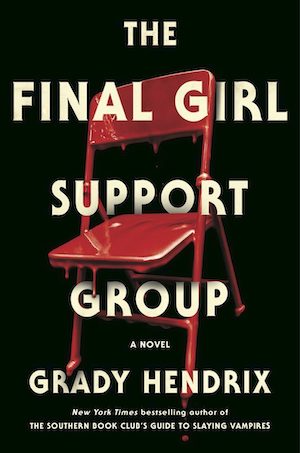

The Final Girl Support Group

But the first fully committed serial killer POV novel seems to be Dorothy B. Hughes‘ In a Lonely Place (1947) which got made into a swanky Hollywood film that had absolutely nothing to do with the book, which was way too unsavory for Tinsletown. Trapped inside the POV of struggling writer Dix Steele, the most phallic showbiz handle since Peter O’Toole, In a Lonely Place follows Dix as he floats through post-World War II Los Angeles, looking for his lost combat high. He has some drinks with his former comrade in arms, now a cop, makes dinner party chitchat, and flirts with the redheaded sugarbaby living in his apartment complex. Only slowly does the reader realize that the book’s cocktail party chatter about strangled women showing up all over L.A. might actually be about Dix, and the fact that he’s murdered some of his victims right under the reader’s nose makes everything feel even clammier.

Hughes’ radical novel thoroughly eviscerated toxic masculinity and it’s a shame the book isn’t better known, but it preceded a big wave of first person (or third person limited) serial killer novels from Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me (1952) to Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and on to Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley. Bloch’s Psycho appeared in 1957 but the crown jewel of this wave of writing came with Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) a book told entirely from the perspective of an 18-year-old girl who may or may not have poisoned her entire family. A better stylist than Bloch, Jackson delivered probably the greatest murderer POV novel of them all.

In the meantime, actual serial killers weren’t slacking. H.H. Holmes wrote confessions of his crimes for various newspapers and after he was executed in 1896 they were published as The Strange Case of Dr. H.H. Holmes. Less lucky was Carl Panzram, imprisoned in 1928 after a multi-year murder spree, who wrote his autobiography but didn’t see it published until 1970. The nadir of serial killer books written by actual serial killers came in 1984 when Jack Unterweger, an Austrian, wrote his autobiography, Purgatory or the Trip to Jail — Report of a Guilty Man, which became a bestseller. Unterweger used his book to blame his mother for his killings and to express remorse. Fans like Günter Grass and Elfriede Jelinek demonstrated their poor judgement by lobbying for Unterweger’s release and he received his freedom in 1990, became a television host and reporter, and murdered at least eight more women.

Serial killer points of view in novels had gotten more grotesque with Ramsey Campbell’s lurid and hallucinatory The Face That Must Die (1979) whose distorted visuals were in part inspired by his experience taking care of his schizophrenic mother. Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory (1984) held a dark mirror to Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle with its teenaged narrator who, like Jackson’s Merricat, is a murderer and practices occult rituals to protect himself. Unlike Merricat, however, Banks’ narrator has had his penis bitten off by a dog.

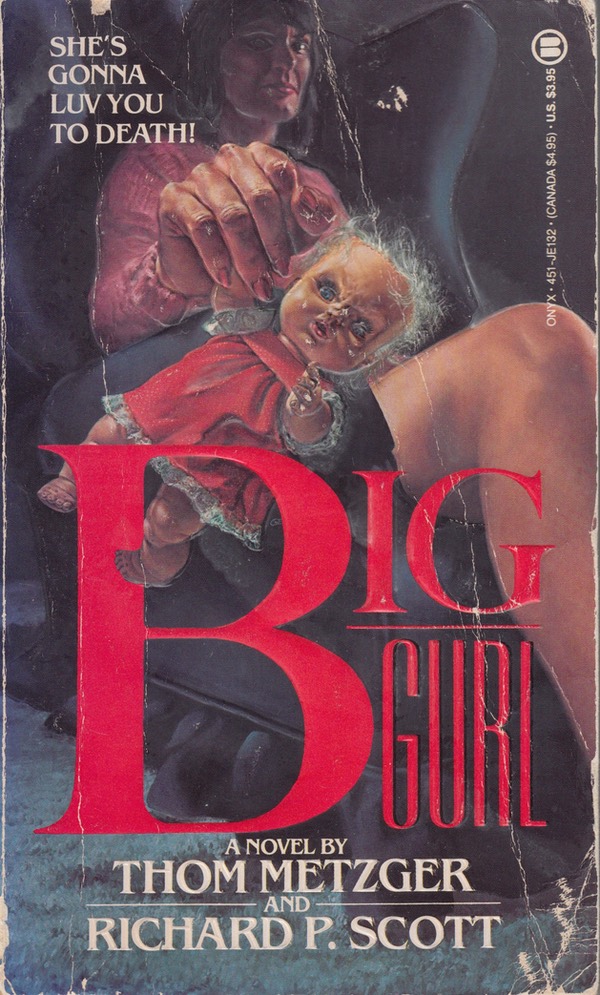

The Nineties saw an explosion in serial killer chic, building to a singular disasterpiece, Big Gurl (1989) by Thom Metzger & Richard P. Scott. Big Gurl came out from Onyx, a horror paperback original imprint of New American Library, and it’s rigorously devoted to telling its story entirely from the point of view of Mary Cup, aka Big Gurl. As she says of herself, “Come on, tell Big Gurl the truth. Isn’t she just a breathless Miss America?” We’re not sure how big she is, but when people annoy her she lifts them off the ground with one hand, sometimes by their nostrils. When she selects a victim she simply shouts at them until they meekly follow her to their doom, sometimes weeping quietly.

We first meet Big Gurl sitting in the mud, jamming worms into her ears. She sees the power company man reading her meter and decides that he’s been sent to spy on her for her father or, as she puts it, “This is a Grade Eleven Total Emergency Return of Baddest Dad Alert.” She drags the meter reader into the garage of the building where she lives, jams a corset over his head, sticks a vacuum cleaner in his mouth, electrocutes him for a while with a frayed extension cord, strings him up from the ceiling, blows fertilizer in his face, stuffs his mouth with newspapers, and then buries his barely-alive body up to its neck on a golf course. The worst part of it is, she doesn’t shut up once.

“Hey! That no fair! Big Gurl closing her eye for just one little seconds when all the sudden that skeleton hand sticking out of the TV again grabbing like crazy up and down her most gorgeous of all time sex-is-a-beautiful-thing-body. And just because it stroke of midnight don’t mean all you scary Dracula monkeys can jumping out the TV and stealing her priceless too-much-glamorous furniture behind Door Number One Two or Three and who knows which one has the most exciting heartbreak beautiful prize of all?”

It is very annoying.

Her social worker, Vernon Negrescu, is in love with her and she keeps encouraging him to murder his mother so they can live together. Vernon was a porn actor whose stage mother accompanied him to porn sets and he spends most of his time chastely worshiping Big Gurl. Meanwhile, Big Gurl spends her days stuffing people’s framed photographs down her pants. There’s kind of a plot involving her father looking for her and Vernon becoming increasingly desperate that Big Gurl will leave him, but by the end of the book she’s moved in with him and is happily filling his basement with the corpses of her victims. As she says, “If she don’t be having lots of fun what’s the use of being Big Gurl?”

If Stephen King’s Misery annoyed you with Annie Wilkes’ “cockadoodies” and “fiddely-foofs” then Big Gurl will make you homicidal. Then again, maybe its authors were ahead of the curve? The early Nineties saw a wave of over-the-top, anything-goes, alienated, in-your-face, plots-are-for-losers, gore-gore serial killer books that every hipster needed to display on their bookshelf. Joyce Carol Oates won awards with her edgelord Zombie in 1995, which doesn’t do anything that Big Gurl didn’t do first. And Bret Easton Ellis became a cultural touchstone with American Psycho in 1991 which, again, tilled those same fields. So give credit where credit is due: Big Gurl got there before everyone. Besides, do either Oates or Ellis have the guts to write a touching scene to rival the one where Vernon confesses to Big Gurl that he got his start in porn after a vision of Elvis with a chihuahua growing from his crotch appeared to his mother?

Grady Hendrix is the award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, along with a bunch of other books and movies. His new novel is The Final Girl Support Group (out July 13) and you can find more dumb facts about him over at gradyhendrix.com.

Not exactly a serial killer story, but I have to mention “The Distributor” by Richard Matheson, a short story. He is a guy who moves into a suburban neighborhood and turns everyone against each other. You are never sure if the guy is crazy or if he is the Devil himself.

A very good short story by Robert Bloch about a guy going crazy is “See How They Run.”

I started reading this as I have enjoyed Poe (and Dostevsky) and….I was not expecting it to go where it did, lol. Wow.

A weird, slightly offbeat chance – back in the 90s there was a bunch of Star Wars anthologies which told points of view from minor characters in stuff like the cantina, Jabba’s palace ,etc. I always remember the tale of Dannik Jerriko (the guy smoking a pipe in the cantina) freaking me out as he was an ‘energy vampire’ serial killer type who really wanted to kill a Force user so he could savor their essence.

@2 – I reached the conclusion that the “essence” that Dannik Jerriko was craving is sinus mucus, basically making him a snot vampire.

As usual, Roger Zelazny did one (sort of) in The Night in the Lonesome October. I just love this scene: